Story Board : Saul Bass

Frames from the shower sequence storyboard

The shower scene comprises of 78 shots edited into a 45 second segment and took 7 days to complete.

Saul envisioned a fast-cut, impressionistic murder, with no blood until the very end when it swiris down the drain. The script suggested certain image: others he invented, like the pulling down of the shower curtain.

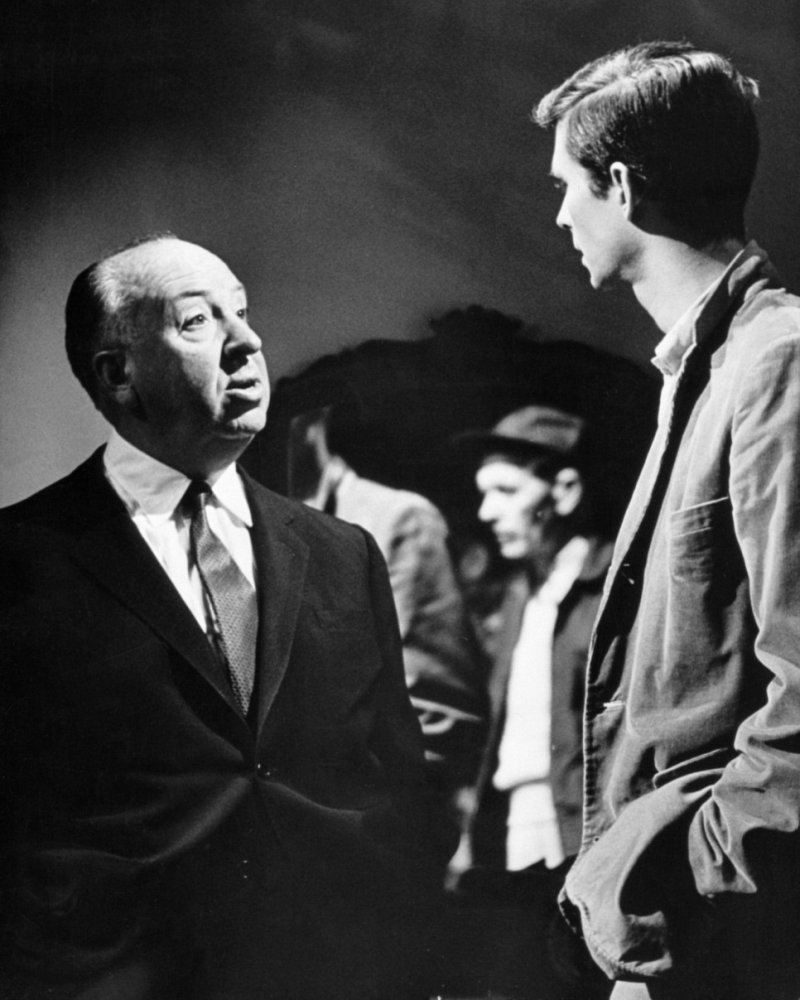

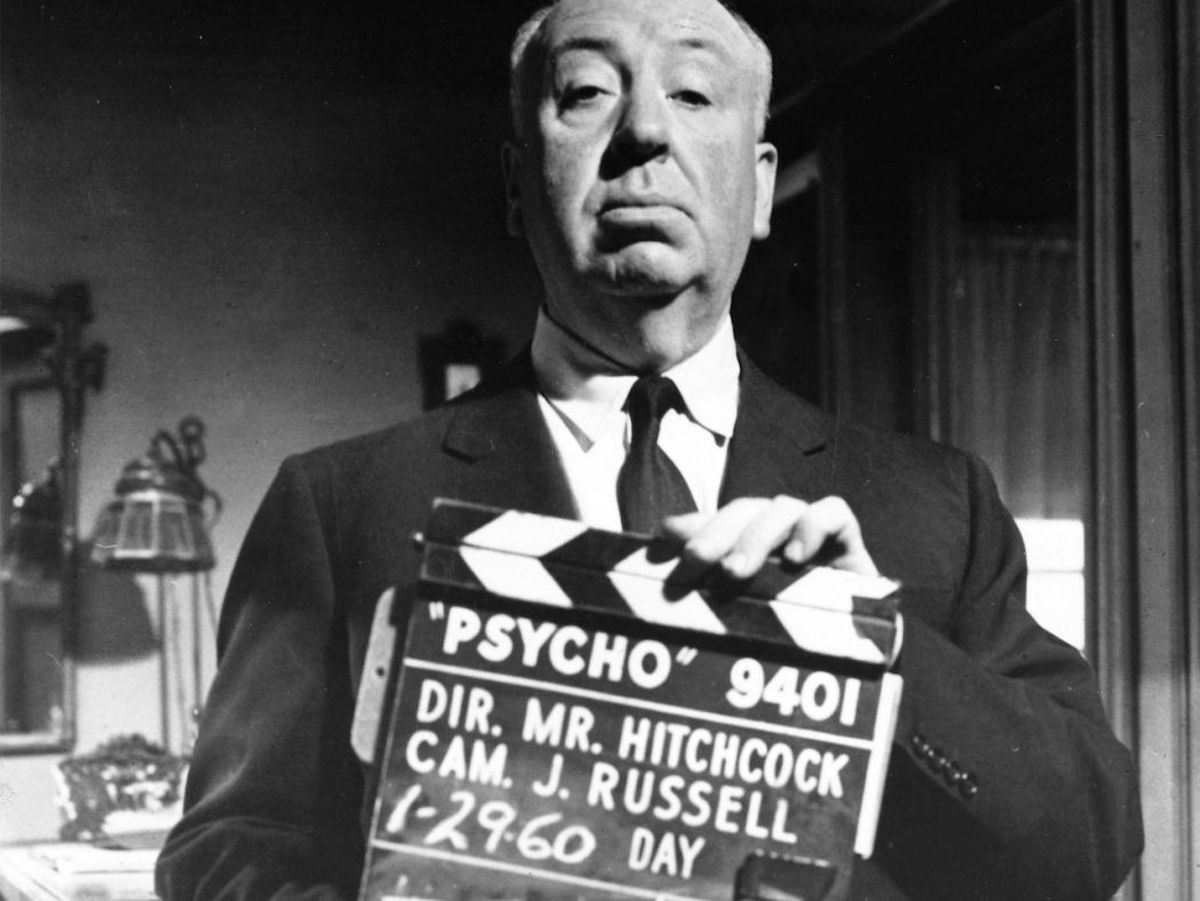

Contact sheet of photographs taken on set of Psycho: Saul Bass, Alfred Hitchcock, and Janet Leigh, 1960.

The Case for Bass: Visualization and Storyboards

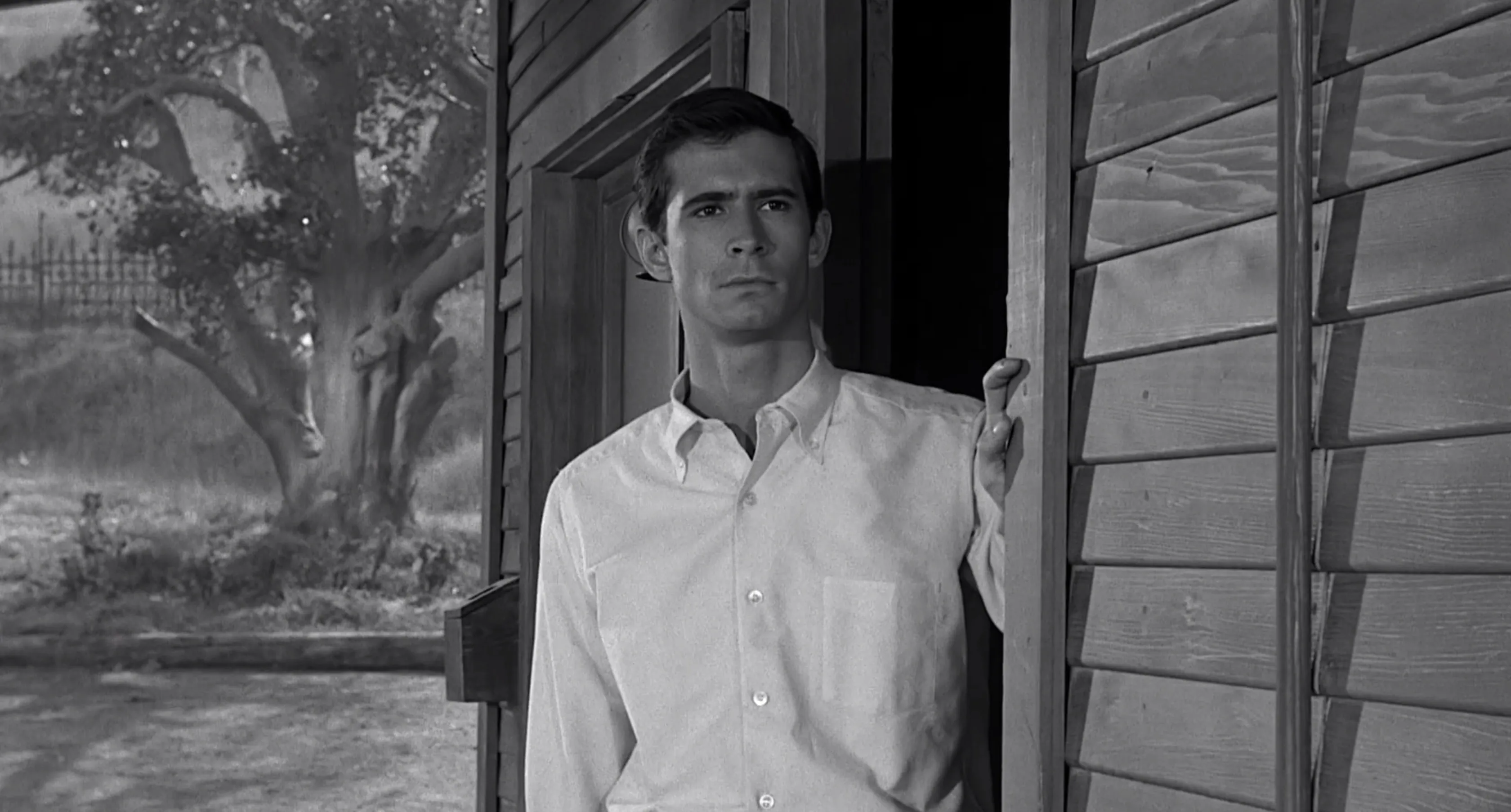

Despite Hitchcock’s strong implication that Bass did not work on the shower scene, a great deal of evidence exists to the contrary; from testimonies by people working on the film to the visuals themselves, it points to Bass as the person who visualized and storyboarded that section of the script, a section prioritized by Hitchcock for special handling because he knew that audience expectations would be shattered by the disruption of cinematic conventions involved in murdering the attractive young “heroine” less than halfway through the film.

This was not the first time Hitchcock had brought in an artist to create a special sequence within a film; the Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali had created a dream sequence for Spellbound (1945), and American abstract expressionist John Ferren did the same for Vertigo. The latter work appears amateurish when compared with Bass’s title sequence for the same film, a comparison apparently not lost on Hitchcock.

According to Stephano, Hitchcock told him, “I’m going to get Saul Bass to do a storyboard for the shower scene so we know exactly what we’re going to do,” and Stephano sent Bass each section of the script as it was finished. Janet Leigh told Donald Spoto that “the planning of the shower scene was left up to Saul Bass, and Hitchcock followed his storyboard precisely. Because of this . . . [the shooting] went very professionally,” and she told Rebello that “Mr. Hitchcock showed Saul Bass’s storyboards to me quite proudly, telling me in exact detail how he was going to shoot the scene from Saul’s plans”. Another crew member who confirmed that Bass visualized the sequence was Psycho art director Robert Clatworthy, and we know from Harold Adler, who worked for National Screen Services, the company that produced the Bass/Hitchcock titles, that Bass storyboards were always “very complete and precise.”

Other evidence pointing to Bass as designer of the shower scene includes the very substantial sum of $10,000 paid to him for the consultancy — more than Hitchcock paid for the rights to the novel. Hitchcock’s financial advisers argued against paying Bass so much because Hitchcock was using his own money to produce the film (the budget for which was just over $800,000), but Hitchcock vetoed all suggestions that Bass’s fee be lowered. Bass’s fee as a visual consultant equaled that of supporting actor Vera Miles, and his weekly rate of pay was three times that of the film editor (Tomasini). The total paid to Bass for all aspects of his work on the film came to nearly $17,000, just short of the $17,500 fee paid to Hermann for scoring the entire movie, and also to Stefano for the script.72 Furthermore, Hitchcock was a director who gave art directors and other creative people considerable artistic leeway. Further evidence becomes apparent as the narrative unravels.

For Spielberg the “flat Venetian-blind credits that came charging in from all sides of the screen start Psycho like a knife to the throat,” and something of that sensation is echoed in the shower sequence. Some of the images were prompted by the script; others, including the pulling down of the shower curtain, came from Bass’s imagination. Bass translated the script into powerful visuals, designing a highly stylized murder, fast cut after fast cut in simulation of the frenzy of the act itself — an act the audience does not see. Skilled at the visualization of ambiguity and metaphor, Bass used montage, tight framing, and fast cutting to render a violent, bloody murder as a ritualized, impressionistic, near bloodless one.

The dramatic intensity was reinforced by repetition. As Bass put it, “She’s taking a shower, taking a shower, taking a shower. She’s hit-hit-hit-hit. She slides, slides, slides. In other words, the movement was very narrow and the amount of activity to get you there was very intense. That was what I brought to Hitchcock. By modern standards, we don’t think that represents staccato cutting because we’ve gotten so accustomed to flashcuts. As a title person, it was a very natural thing to use that quick cutting, montage technique to deliver what amounted to an impressionistic, rather than a linear, view of the murder.”

Hitchcock felt uncertain about Bass’s bold conception, fearing audiences might not accept such a stylized and staccato-like, symbolic, and abstracted sequence. Bass recalled, “Having designed and storyboarded the shower sequence, I showed it to Hitch. He was uneasy about it. It was very un-Hitchcockian in character. He never used that kind of quick cutting; he loved the long shot. Take the opening shot in Psycho, where the camera moves over Phoenix, over the buildings, closes in on a building, into a window and into a room where Janet Leigh and John Gavin are making love. That sort of camera move was his signature. My proposal was from a very different point of view.”

That Hitchcock was not completely convinced about the concept worried Bass. “His misgivings made me a bit nervous too,” he recalled, “so I borrowed a camera (a little Eymo wind-up with a twenty-five foot magazine) and kept Janet Leigh’s stand-in on the set after the day’s shooting. I put a key light on her and knocked off about fifty to a hundred feet of film. Then I then sat down with George Tomasini and we put it together following my storyboards, not worrying too much about finesse — just wanting to see what the effects of these short cuts would be. We showed it to Hitch. He liked it.”

In the end, Hitchcock gave it his approval but wanted two additions: a spray of blood on the chest of Marion Crane/Janet Leigh as she slides down the tiles, and a close-up of her belly getting stabbed. When Philip Skerry interviewed Hilton Green, Hitchcock’s assistant director, he pressed him hard about the latter shot, insisting that the knife penetrated the skin. Green was adamant that no such thing was shot, stating, “We never did a thing like that. And that was before the computer things where you could do things like that”; when pressed further he said, “We never shot it. According to Bass, the effect of a knife stabbing the belly was achieved by pulling the knife away from her skin, reversing the shot, and cutting away just as it touched the skin.[79] Such knowledge suggests that Bass was closely involved with the filming of the shots.

When I asked Bass how he felt about the additions, he stated that, despite his huge respect for Hitchcock, “deep down I was not really happy”: “It impinged on the purity of the concept, a ‘bloodless’ murder with no knife contact. My idea was to hold back the horror of showing blood until the very end when it would be seen swirling down the drain. I was surprised at my response. I was in awe of Hitch. How could he be wrong? I told myself it did indeed make the sequence more effective.” He paused for a long time, deep in thought, before adding, “Sometimes there’s a little voice inside me that says it was better without them.”[80] In terms of design, that was probably the case; within the film, however, Hitchcock’s decision to add more blood and overt violence undoubtedly raised the sensational tone of the sequence and helped ensure its infamy.

As filmed, the scene closely follows the storyboard, and all of Bass’s images were probably shot. In the final edit, Hitchcock left out some images and moved others around, but the resemblance between the original design and the finished sequence is quite remarkable, especially for Hitchcock, who greatly relied on creative editing. Visual clues are the overall modernist design sensibility of the piece as well as more specific imagery, such as the transition from the drain in the bathtub to Leigh’s eye, which recalls the unsettling eye in Bass’s Vertigo title sequence and the huge eye in Bonjour Tristesse, while Leigh’s desperate outstretched hands recall those of concentration camp inmates in the opening of The Victors. The circular form of the showerhead and drain are seen in several Bass titles, including Attack!, Walk on the Wild Side, The Victors, and Grand Prix, while the Walk on the Wild Side sequence is a good example of the power of the close-up in a short, tight sequence.

Evidence, scholarship and debate: Saul Bass and the shower scene in “Psycho”

The evidence, scholarship and debates: Saul Bass and the famous shower scene in “Psycho.”

designobserver.com

'스토리보드 Storyboard' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [스토리보드] 택시 드라이버 총격 시퀀스 Taxi Driver Shooting Scene (2) | 2023.04.23 |

|---|---|

| [스토리보드] 에이아이 A.I. Artificial Intelligence (0) | 2023.03.08 |

| [스토리보드] 기생충 계단 시퀀스 Parasite Stairs Scene (1) | 2023.01.28 |

| [스토리보드] 블레이드러너 2049 오프닝 시퀀스 Blade Runner 2049 Opening Scene (0) | 2023.01.27 |

| [스토리보드] 엑스맨 2 나이트크롤러 백악관 시퀀스 X-Men 2 Nightcrawler White House Attack Scene (0) | 2023.01.13 |